Markov Chains and Me

Today I’ve decided to do a little personal challenge. I’m going to take a mathematical idea that I know very little about (I’ve got a pretty huge pool to choose from given that criterion), and see how much I can learn and summarize here in one hour.

I’ve decided to learn about the Markov chain. Some context on that choice: once upon a time, Twitch played pokemon. If you didn’t catch that when it happened, all that you need to know is that all the actions taken by the character were driven by the Twitch chat, so for the most part, the whole adventure was a beautiful chaos - and it made doing certain things that required a series of correct inputs in a row take a lot longer than if one person was in control.

I was perusing some threads about estimating the probability of finishing certain parts of the game in certain amounts of time, and someone brought up the Markov chain, and said that its a pretty neat tool for examining such behaviors. While deeply interested in the application, I wasn’t too keen on actually learning about it back then. It stuck with me ever since, and today is the thrilling day.

Let’s start with a confusing analogy and without addressing how it relates to the topic. Think of yourself in a maze. There’s two characteristics that are important to this maze situation: where you are, and where you can go. Here’s a maze that starts at s and ends at e, for reference.

#####################

#s# #

# ### # ### # # # # #

# # # # # # # # #

# # # ######### #####

# # # # # #

# # ####### # ##### #

# # # # #

### # # # ####### ###

# # # # e#

#####################

Standing at s, you occupy that square or spot or whatever you want to call it. You have only one option for movement: downward, as any other direction goes straight into a wall. Can’t walk into those. At least not with my crappy attitude! Be better than me. Believe in yourself to go through walls.

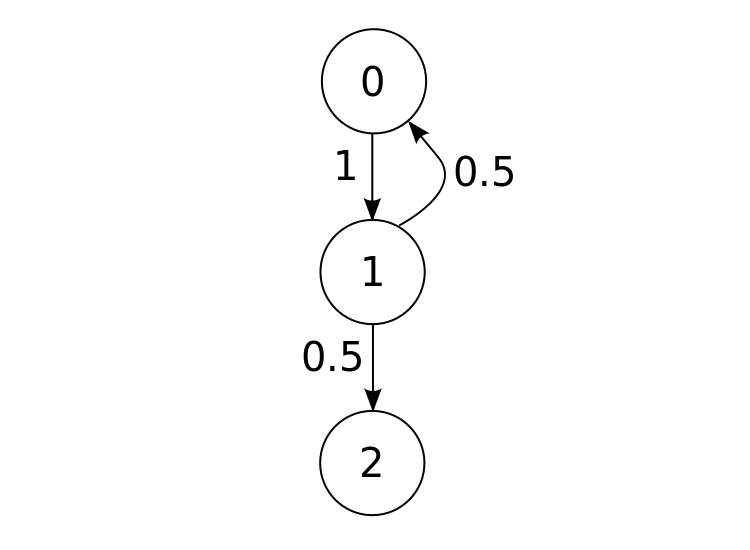

From the next spot, you can go back where you came, or you can go down again. And so forth for every spot in the maze. This whole “process” of walking around this maze can be represented as a Markov chain. Assuming you randomly select which way to walk from a given spot, those first two movements would look like this:

Where positions 0, 1, and 2 are as marked here:

#####################

#0# #

#1### # ### # # # # #

#2# # # # # # # #

# # # ######### #####

.

.

.

And, the number associated with each “choice” - 1, 0.5, and 0.5 - is the probability that choice will be made (here it is random for each choice, so if there are four ways to go, each will have probability 0.25, and so on). This doesn’t need to be the case. The probability of these choices depends on the nature of your system, and all that jazz. For all I know, your favorite direction is left and so you always have at least an 80% chance of going left when you’re mazing on the weekends.

There’s an important distinction we need to make about these choices: in a real maze, you probably wouldn’t go back the way you came, since you know it leads to dead end. If you do want to go back, well, you might want to rethink your maze solving strategies. That, or you’ve ascended beyond the tangible shackles of the maze. You pass through walls like a hot knife through butter. The walls are meaningless, and can no longer contain your righteous spirit.

Markov chains have no “memory”, so each decision is based solely on the current position. In the context of our model above, square 0 is on equal grounds with square 2 for movement from square 1. This is simply a characteristic of the Markov chain - the probability of a state change from each state is not influenced by the state changes you made in the past. Live in the present, friends.